I present here a short essay on Italian army battles on the Isonzo front on the occasion of the Centennial commemorations of the Great War.

“This Was a Strange and Mysterious War Zone”

“This was a strange and mysterious war zone […] The Austrian Army was created to give Napoleon victories; any Napoleon. I Wished we had a Napoleon, but instead we had ‘II Generale Cadorna,’ fat and prosperous and Vittorio Emmanuele, the tiny man with the long tin neck and the goat beard… ( See E. Hemingway, “A Farewell to Arms”, New York, 1929, p. 38).

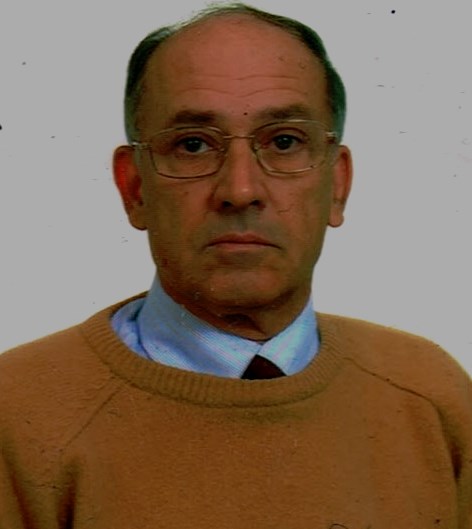

Between 1915 and 1917, there were 13 battles of the Isonzo River, and the Supreme Commander was General Luigi Cadorna, the son of Raffaele Cadorna, commander-in-chief of the Italian army that occupied Rome in 1870 [in the same year Rome was consecrated as the capital of Italy]. Luigi Cadorna was born at Pallanza in 1850 and fast (at ten years old) entered the Military Academy in Turin (1).

It is certain that General Cadorna caused many problems

By general consent, and although some qualified observers recognized that the Italian Army's equipment was in many aspects insufficient (both the Italian weapons were effectively obsolete and munitions sometimes insufficient), it is certain that General Cadorna caused many problems because he had no concern for his soldiers. During the battles of the Isonzo, the strategies performed by General Cadorna (64 years old in 1914 ) were essentially a foregone conclusion and, moreover, unjustified and unnecessary disciplinary measures had been inflicted by him. With these premises the 13 battles of the Isonzo River Valley were performed with the only result of sending thousands and thousands Italian soldiers off to the slaughter. The battles of the Isonzo were one of the most decisive proofs of the enormous sacrifices to which the Italian soldiers of the Great War were submitted .

Scenery of the Battlefield

The Isonzo front shows a wide scene of huge and inaccessible mountains. A precipitous mountain barrier, rich in Alpine peaks, increases beyond the Isonzo river. Gorizia is situated on the left bank of the Isonzo and it may be seen between insuperable peaks and plateaus . On the north of Gorizia there is the Bainsizza plateau, South of the city the Carso plateau, while the Julian Alps run West of the Isonzo River Valley . The Austrians barricaded such natural fortifications and the view took the breath away. The machine guns gave no rest to the Italian troops in their hard advance with frontal assaults against mountain peaks obstinately defended by the Austro-Hungarian soldiers, and the Alpini Corps suffered tremendous losses.

Italian Attack on Monte Nero: The first offensive: about 20,000 Italian soldiers died

The Austrians locked themselves in Monte Nero, and the Italian army needed to attack this place of great strategic importance because of Monte Nero provided a bird’s-eye vision of every enemy advance night and day and round the clock. The Italian troops attempted numerous attacks on Monte Nero at the beginning of June, 1915, but they suffered severe losses from the Austrian defenders, who were in a very advantageous and fortified position against the Italian soldiers.

However, by June 16th the Austrians entrenched on Monte Nero were decisively beaten by the Italian Army. But the Austrians were also well entrenched on Mount Cucco, and they entirely controlled the Isonzo Valley. The Italian soldiers conquered Mount Cucco but the win was very difficult and costly, because, according to M. Thompson, they reported 500 dead and about 1000 wounded. In the first month of the Isonzo Valley offensive, the Italians lost about 20,000 soldiers (2).

The Second Offensive: about 1,916 killed , 11,500 wounded

Although the Italian soldiers were mown by the modern machine guns, General Cadorna attempted new offensives along the Isonzo in 1915. The Second Offensive began on July 18 and endured until August 3, 1915, with the attack to the Carso, near the city of Gorizia. General Cadorna maintained the same strategy with massed frontal assaults, but Insufficient artillery supplies and a spray of bullets of machine guns increased death toll. The Italian losses were 1,916 killed , 11,500 wounded and more than 1,600 were missing, while the Austro-Hungarians suffered 8,800 dead (3).

The Third and The Fourth Offensive

General Cadorna recalled reservists and more artillery and new men were added to the first lines. In the meantime the Austrians strengthen their defensive positions. The Third Offensive began with massed assaults and tremendous artillery bombings from the Italian lines. The main military targets were both Gorizia and the Austrian fortifications. As a result, the Third Offensive ended on November 4th, and knocked out about 60,000 Italian soldiers.

The Offensive Launched by General Cadorna Cost the Italians About 40,000 Losses.

On November 9, 1915, the Alpine troops attempted new frontal assaults against the well-entrenched Austrian soldiers, but troops’ advance was hindered be the artillery fire, barrage of the machine guns, and barbed wire fences. Besides, winter became intolerable to soldiers in the area on which the battles were fought, and the offensive was over. The fifth offensive launched by General Cadorna cost the Italians about 40,000 losses while the Austrians lost about 20,000 soldiers . In June 1916 the Austrians unleashed a phosgene attack on Italian lines with devastating effects. Both phosgene attack and artillery caused more than 7,000 casualties.

The Seventh, Eighth, and Ninth Offensives on the Isonzo Front

The Italian army faced a ghastly situation for artillery fire, inexpugnable entrenchments and phosgene attacks when General Cadorna launched the Fifth Offensive (1916) which caused around 8,000 casualties. During the sixth offensive, the capture of Gorizia cost the Italian soldiers about 30,000 casualties. The Seventh, Eighth, and Ninth Offensives caused more than 140,000 causalities. During the Tenth Offensive, on the Carso, the Italians suffered 150,000 casualties, and during the capture of the Bainsizza Plateau they lost about 160,000 soldiers (4).

The Explanations of the Italian Collapse Along the Isonzo River Valley

Moreover, General Cadorna resorted to measures against his soldiers (with decimation, the execution of every tenth soldier) to enforce discipline. But, overall, he failed to adapt to the changing nature of combat and the nature of environmental problems [high mountain passes], because of, along “this strange and mysterious war zone”, as E. Hemingway said, trench warfare on the Isonzo Front impeded to have room for a war of maneuver. Automatic machine guns, phosgene gas exposure and cannons were a lethal weapon because of the rocky ground and its narrow passageways. The battleground is consequently part of the explanation of the Italian collapse along the Isonzo Valley which led to the inevitable massacre of the Italian mountain troops in 1915, 1916 and 1917 .

The “Foolish Strategy” of General Cadorna and the ' Crazy War '

Professor Isnenghi said that General Cadorna “was no worse than other generals of the Great War”.

It is true.

General Cadorna was 67 years old in 1917, and, after all, he was almost contemporary with General Joffre (62 years old in 1914), General Conrad von Hötzendorf (64 years old), General Moltke ( 66 years old) and General Kitchener (64 years old), but, as many his colleagues, he was linked to obsolete war strategies which were carried out in the 19th century. However, while the Austro-Hungarian High Command, after the heavy defeat and tremendous losses on the Eastern Front against the Russians, [the Austro-Hungarian Army lost about 700.000 officers and soldiers] CHANGED ITS STRATEGY (5), General Cadorna had no regrets about his “foolish strategy”. Indeed, Italian army would require new strategies and several new officers, such as the young Rommel, who, thanks to his new strategic principles, achieved legendary fame during the battle of Caporetto, the major Italian defeat of 1917 [The defeat of Caporetto cost the Italian army about 10,000 dead] (6).

Notes

1) R. K. Hanks, “Cadorna, Luigi”, in “The Encyclopedia of World War I”, edited by Spencer C. Tucker, ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara, California, 2005, Vol. I, p. 247.

2) M. Thompson, “La guerra bianca. Vita e morte sul fronte italiano 1915-1919”, Milano, Il Saggiatore, 2009, pp. 86-87.

3) G. Tomasoni, “Prima e seconda battaglia dell’Isonzo” in “La grande guerra: raccontata dalle cartoline”, Arca, 2004, p. 127.

4) About the Italian losses on the Isonzo Front, See: J. R. Schindler “Bainsizza Breakthrough” in “Isonzo: The Forgotten Sacrifice of the Great War”, Westport, Praeger Publishers (United States of America), 2001, pp. 219 ff. According to J. R. Schindler, Luigi Cadorna “showed little concern for his soldiers” (p. 62).

5) On the new strategies performed by the Austro-Hungarian High Command after the defeat on the Eastern Front in 1914, See: R. Lein, “A Train Ride to Disaster: The Austro-Hungarian Eastern Front in 1914”, in “Contemporary Austrian Studies”, University of New Orleans Press, New Orleans, 2014, p. 124). The expression “Foolish Strategy” is by R. Lein. General E. Caviglia said that the Italian offensive actions of 1915 were “a crazy war” [“Purtroppo […] la ‘guerra da pazzi’ continuò per tutto il 1915” (Unfortunately [...], the ' crazy war ' continued throughout 1915] ( See E. Caviglia, “Diario, aprile 1925-marzo 1945”, Roma, G. Casini, 1952, p. 116). About General Luigi Cadorna's strategy, See: L. Cadorna, “Attacco frontale e ammaestramento tattico” [=”Frontal Attack and Tactical Training”], in “Comando del Corpo di Stato Maggiore. Ufficio del Capo di Stato Maggiore dell’Esercito. Circolare n. 191 del 25 febbraio 1915, Roma, Tipografia Editrice ‘La Speranza’, 1915” ( Free PDF book by R. Bagna in It.Cultura.Storia.Militare On-Line: http://www.icsm.it/articoli/documenti/docitstorici.html. Dottrina e Regolamenti).

6) G. V. Cavallaro, “The Beginning of Futility”, Library of Congress, 2009, p. 230. See also J. R. Schindler, “Caporetto”, p. 243 ff. and “Battle of Caporetto”, in Wikipedia, note 2.

I testi, le immagini o i video pubblicati in questa pagina, laddove non facciano parte dei contenuti o del layout grafico gestiti direttamente da LaRecherche.it, sono da considerarsi pubblicati direttamente dall'autore Enzo Sardellaro, dunque senza un filtro diretto della Redazione, che comunque esercita un controllo, ma qualcosa può sfuggire, pertanto, qualora si ravvisassero attribuzioni non corrette di Opere o violazioni del diritto d'autore si invita a contattare direttamente la Redazione a questa e-mail: redazione@larecherche.it, indicando chiaramente la questione e riportando il collegamento a questa medesima pagina. Si ringrazia per la collaborazione.